Can you safely remove an oil and gas rig from the ocean? Gippsland is about to find out

Australia will aim to decommission 5.7 million tonnes of material from offshore rigs over the next 30 years.

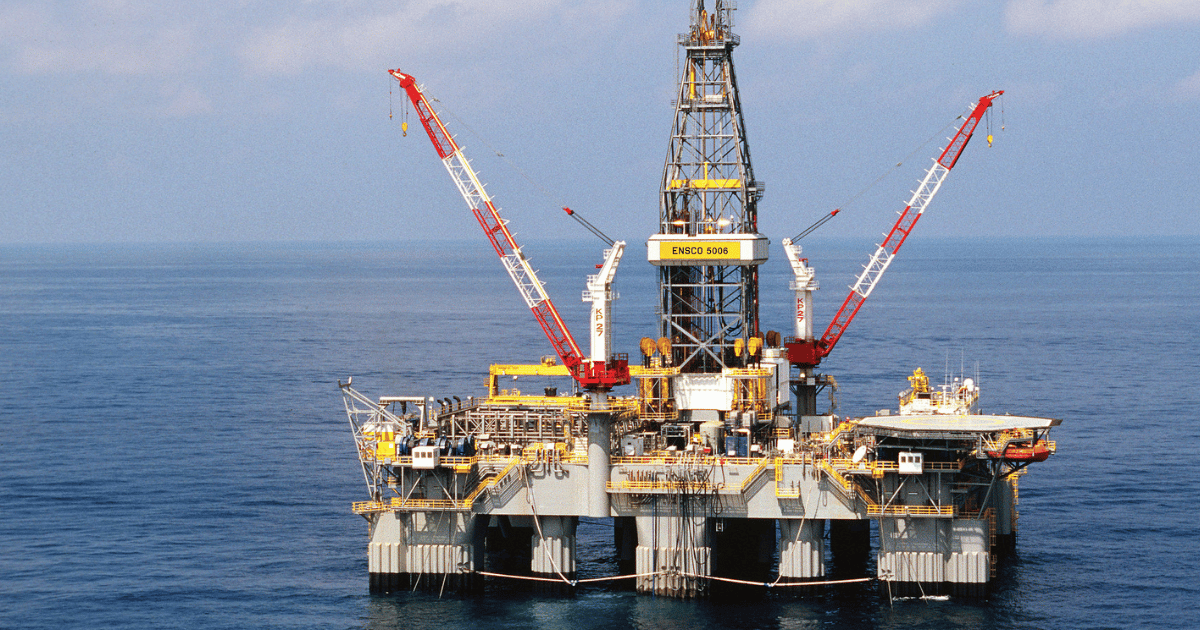

They rise from the seabed towards the sky like a giant Meccano construction, a mess of steel, platforms and cranes - and their time is coming to an end.

As Australia moves towards net zero, offshore oil and gas rigs are being decommissioned. It’s a process that will take decades.

But while environmentalists are pleased to see them go, the massive undertaking of removing these rigs and their concomitant infrastructure from the ocean is leading to a new set of concerns about surrounding wetlands, animal life and fisheries.

By the time the majority of Australia’s offshore oil and gas rigs are decommissioned over the next 30 years, 5.7 million tonnes of material will need to have been removed from our oceans, and then processed.

It’s the equivalent of 110 Sydney Harbour Bridges.

The federal government says the process of decommissioning involves securely plugging oil and gas wells, and removing what may be hundreds of kilometres of pipe and flow lines.

Steel structures with large production decks embedded in the sea floor need to be dismantled, and floating oil and gas production facilities and their anchors will need to be removed.

The materials will then need to be transported to ports and dismantling yards, with steel, plastics and other materials recycled, and waste materials sorted, treated and disposed of safely.

Why are we decommissioning oil and gas rigs?

Australia is transitioning away from fossil fuels like oil and gas towards renewable energy as part of the federal government's commitment to reach net zero emissions by 2050 and keep global warming from human induced climate change below 2C.

The Bureau of Meteorology attributes more extreme weather events, such as increases in the number of heatwaves, number of days in drought and dangerous fire days, to rising global temperatures from greenhouse gas emissions.

As part of that transition, offshore oil and gas rigs are becoming redundant, and according to ExxonMobil 13 of its 19 platforms in the Bass Strait are no longer producing oil and gas.

Gippsland’s Barry Beach a standard bearer?

Gippsland’s Barry Beach could be the location of Australia’s first ever offshore oil and gas rig decommissioning, and may therefore set the standard for the process around the country.

According to the state government, there are 23 offshore oil and gas rigs in Bass Strait with over 600km of pipeline. Esso, the trading name of oil and gas company ExxonMobil, owns and operates 19 of these rigs.

Esso has submitted a referral to the federal government, requesting permission to dismantle and decommission 13 of its oil and gas rigs at the Barry Beach Marine Terminal.

This submission is the first of three that ExxonMobil has to make under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act. The first pertains to preparing a site at Barry Beach to receive the rigs.

The second relates to the transport of the rigs to Barry beach and the third referral is to begin work breaking down the rigs.

Under the EPBC Act, anyone whose project could impact the natural environment or heritage sites is required to submit a written request to the Environment Minister who decides whether the action proposed needs further assessment and approval.

Safely removing the infrastructure

Friends of the Earth Offshore Gas Campaigner Stanley Woodhouse told the Gippsland Monitor that Friends of the Earth and many other environmental groups, including The Wilderness Society and the Australian Marine Conservation Society, want to see complete decommissioning of offshore oil and gas rigs.

“But we want it to come out with really strict government oversight,” he added. “And the community being protected and the environment all being protected. Because whatever happens now in Victoria will be replicated around the rest of the country.”

He accused the federal and state government of being “asleep at the wheel when it comes to preparing for decommissioning”.

Woodhouse said some locals he had talked to didn’t want the decommissioning to go ahead at all, “but a lot of them are actually fine for it to go ahead, if it can be shown by someone other than ExxonMobil, that it's not going to have far reaching environmental impacts”.